>

(image via SIU School of Law)

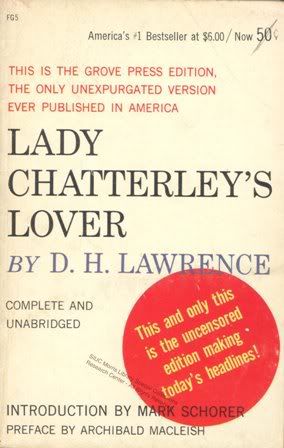

Given the promises made within the bold red circle on the cover, you can imagine our delight when we stumbled upon our parents’ copy of the unexpurgated edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, tucked way, way up high on the top shelf of their bookcase. And, if you happened to read the same tome as an eager youth, you can also appreciate our growing disappointment as we realized the book was a bit more, well, literary than some other titles found in their 1970s-era library.

All of that was possible thanks to a court decision made 50 years ago today–resulting from the efforts of Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset, who sued the US Postal Service for confiscating copies of the uncensored version of the novel, which had long been banned for its explicit descriptions of sex and liberal use of the f-word. As recounted in the New York Times, an attorney hired by Rosset, Charles Rembar, spotted a loophole in an earlier Supreme Court ruling and argued that while a work might be found obscene, it could at the same time present ideas of “redeeming social importance” – and qualify for First Amendment protections afterall.

Though obscenity battles continue on today, a ruling on July 21, 1959 in favor of Grove Press took away the Post Office’s absolute authority to impound and restrict such works. And paved the way for Lady Chatterley’s Lover to find its way to bookshelves throughout America, to be joined later by such subsequent Grove Press gems as the first US edition of The Story of O and “My Secret Life,” the purported erotic memoir of a Victorian gentleman, along with many less prurient offerings over the years.

Barney Rosset’s heroic skirmishes against censorship and the ups and downs of Grove Press are detailed in the recent documentary Obscene: